Children Without Borders

by A. D. Coleman

“More than 117 million individuals have been forcibly displaced worldwide as a result of persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations. We are now witnessing the highest levels of displacement on record.”

— UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, June 2025

“Borders & Boundaries” serves as the chosen theme for this 2026 edition of a long-running, annual, collaborative exhibition of work by a cross-section of Nordic photography students. This collection features emerging picture-makers from Finland, Iceland, and Sweden. Their contributions take the form of triptychs, some in black & white but most in color. And it’s worth noting that, for the first time, taking advantage of what internet technology enables, all of this year’s entries include audiofiles in which the participants talk about their work, personalizing it even further. The dividing lines with which they engage in their images include those between male and female, life and death, human and animal, private and social, safety and danger, anxiety and security, the natural and the man-made, the born and the unborn, even the earthly and the celestial.

There’s no avoiding constant negotiation over where one thing starts and another stops. Arguably, that begins when we exit the birth canal, if not before. In our roles ranging from private individuals to public citizens, we exist within a latticework of overlapping and intersecting territorial definitions. Some take physical form: the surfaces and openings of our bodies, the signposts and fences demarcating where one state, region, or country ends and another begins. Others we term abstractions: gender, sexuality, political affiliation, religion, ethnicity, nationality.

For convenience’s sake, and perhaps to preserve our sanity, we generally think of such delimitations as fixed, permanent, and inviolable. Yet science has taught us that even the subatomic particles composing our unique embodiments operate in a state of constant flux and interchange, as a result of which our cells replace themselves completely every seven years.

By the same token, our mental states — moods, emotions, perceptions, convictions — continuously shift and evolve. Heraclitus tells us we can’t step into the same river twice, while physics suggests that when I go to sleep tonight I will wake up changed tomorrow morning.

As with ourselves, so with the outer world. Beliefs come and go. Taboos emerge and wither. Walls get erected and torn down. Maps get drawn and redrawn. Borders and boundaries prove porous, permeable, and negotiable. In some situations we demand respect for “No Trespassing” signs, while in others we encourage contest and transgression. We have probably functioned within this condition of wishful fixity and actual uncertainty since the first tribe on one side of a mountain met the unexpected tribe on the other side.

What if, this coming year, we drew a line in the sand between what was good for children and what was not? Children come into the world assuming it borderless and unbounded. Perhaps we might strive to reconceive it as did James Baldwin:

“The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.” (“Notes on the House of Bondage,” 1981)

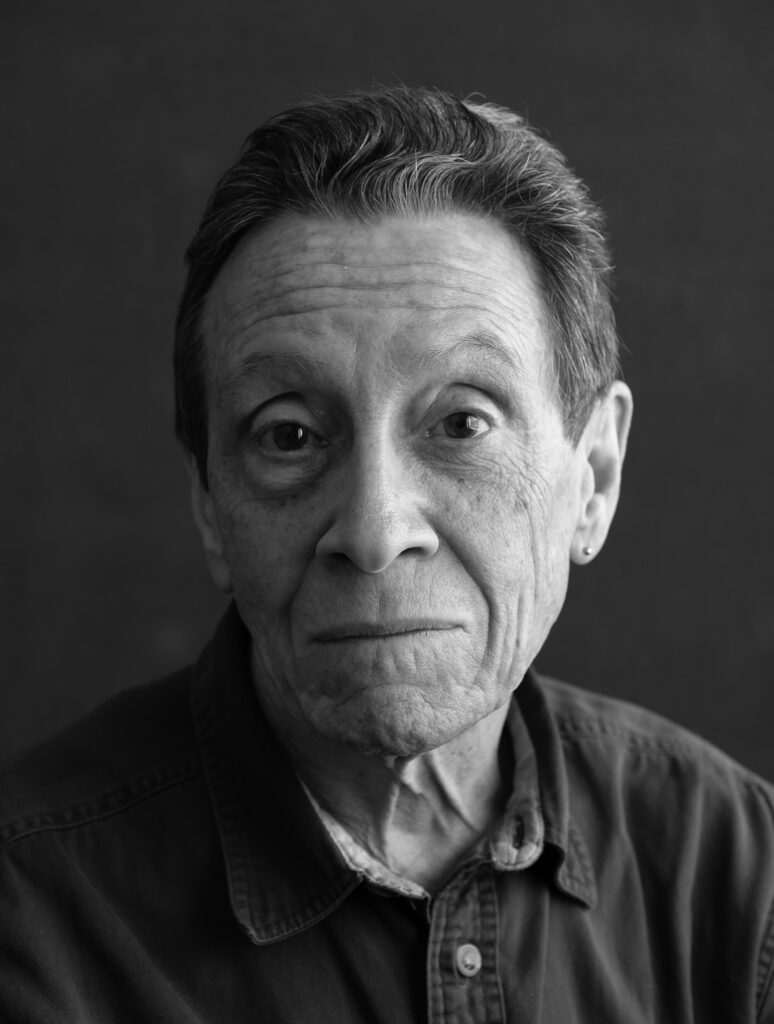

Bio note:

Based in New York, A. D. Coleman currently celebrates his 58th year as a critic, historian, and theorist of photography and photo-based art. His blog, Photocritic International, appears online at tinyurl.com/3r4uuynp.

© Copyright 2026 by A. D. Coleman. All rights reserved. By permission of the author and Image/World Syndication Services, [email protected].